Gropius House

/GROPIUS HOUSE, LINCOLN MASSACHUSETTS 2017

GROPIUS HOUSE

At the center of modernism’s vanguard, German architect Walter Gropius, creator of the world famous Bauhaus school was much more than an architect. He was a trailblazer in the development of modernism and his model of all-encompassing freedom of creative expression and cutting-edge ideas would shape generations. Gropius was also a great connector. He had a penchant for the discovery and development of new talent not only with students, but also colleagues. He surrounded himself with people who had immense skill in their respective fields. László Moholy-Nagy, Josef and Annie Albers, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Joost Schmidt, Marianne Brandt, Eric Mendelsohn, Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer.. Please forgive me for this very partial list, but you get the idea. Marcel Breuer, in fact, would become one of Gropius’ most trusted collaborators and friends following his mentor first to London and later to the U.S.

In 1937 Walter Gropius accepted the appointment to chairman of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Mr. Gropius would make Harvard University go down in history as the first architecture school in the United States to replace traditional Beaux-Arts based curriculum with the Bauhaus teaching methodology.

It has never been easy for me to start anywhere but the start, but I am working on it. This time it is particularly difficult as Gropius is one of the pioneering masters of modernist architecture and his Bauhaus became one of the most powerful influences on design of the twentieth century. So, although this is not the first chapter in the Gropius story, it is an important one.

Walter and Ise Gropius moved to the U.S. from London where they had been living since 1934 ‘on leave’ from Germany. At the invitation of Jack Pritchard, founder of the famed Isokon firm, the Gropius’ moved into the Lawn Road Flats (better known today as the Isokon Building) October of its opening year. As the director of the Bauhaus, Gropius was one of the most highly regarded Isokon tenants. During his time in London he held the position of Design Director of the Isokon Furniture Company until the time he left for the states in 1937.

Our chapter begins when Mr. Gropius decides to accept the position at Harvard University. The time period in which he would help shape another generation of creatives and architects. The beginning of his time in the United States, and more specifically a moment inside his family home in Lincoln, Massachusetts.

The Gropius’ spent some time looking for a home to suit them. They looked at Beacon Hill townhouses and homes in the then countryside towns west of Boston. Not finding quite what they were looking for, but in need of a place to live, they rented a small colonial by a lake in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Lincoln was only about a half hour drive from Cambridge and Harvard University. The landscape was beautiful with forested rolling hills and lakes. The house, however was not quite right. The rooms were very small and although Gropius liked some of the features of these New England homes, the style was not exactly a perfect fit for his modern sensibilities. In Ise’s words: “Then something extraordinary happened.”

If you know Massachusetts, you know the name Storrow. The Gropius’ had a very close friend. An architect who designed most of the Colonial style buildings at Harvard during that time. As the story goes, this friend had a conversation with a very important acquaintance. Her name was Mrs. James Storrow. Helen Osborne Storrow was a prominent philanthropist and patron of the arts. She supported numerous causes, one being the conservation of land. He told her of the new German professor at the Harvard School of Design. He explained that he would like to build his own home but lacked the means to do so. He came up with a proposal. The suggestion was that she offer him one of the plots of land she owned in Lincoln, finance the building of the house and rent it to Gropius. Immediately a deal was struck.

“After the briefest conversation, Mrs. Storrow agreed because one of her principles was that a newly arrived immigrant should always be given a chance to show what he could do best. If it was good it would take root, if it wasn’t it would disappear. But it had to be tried out.” - Ise Gropius remembers Mrs. Storrow

Mrs. Storrow would later extend that same offer to three other Harvard faculty members. Marcel Breuer among them, who with the help of Gropius, received a professor of architecture position at the university. Breuer had an immediate and profound impact on the school. Many of his students would become the most important architects of the next generation.. Wait, I’m drifting. Back to this modernist Harvard Faculty housing made possible by Mrs. Storrow. All four structures were to be built on the property she owned in Lincoln, Massachusetts - a mile from Walden Pond. Yes, that Walden Pond. The one made famous by Henry David Thoreau. She offered to donate the land, fund the building costs, and allow the faculty to rent with the option to purchase. Gropius and Breuer opened a small firm in Cambridge, Massachusetts which Breuer directed. “Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. Associated Architects." Within the next year or so, Gropius and Breuer would design and build three houses. A family home for Gropius, his wife Ise and daughter Ati, a bachelor house for Breuer and another for the sociology faculty member James Ford. Architecture faculty member Walter Bogner would design and build his own home. This cluster of modern houses was unlike anything ever seen in the U.S. at the time. They called it the Woods End Road colony.

Gropius House would be the first built work of the Associated Architects.

Gropius house entrance

Gropius and Breuer worked with a local builder from Concord, Massachusetts named Casper J. Jenney. They wanted to experiment with a balloon framed building and Jenney was familiar with this light wood framed structure. This was especially important to Gropius for two reasons. It would allow the house to fit in with the existing architectural vocabulary of the area, and it was quick to construct with standard factory cut lumber and nails. True to form Gropius decided that all structural items and indoor features such as doors, shelving, glass blocks etc. be chosen from stock catalogs to minimize costs. He also wanted to prove that American mass-produced items could easily be used to create a sophisticated modern design that had not yet been seen here. To create maximum results with minimum means Gropius considered a main factor in producing good architecture. Economic sensibility, simplicity, with a strong focus on mass production were after all, Bauhaus principles. Students would visit the house every afternoon during construction and Gropius would spend time explaining how to use inexpensive materials without compromising quality.

The house’s rectangular forms, flat roof, ribbon windows and lack of ornamentation sits it squarely in the International Style. But Gropius' decision to use typical New England materials and forms; red wood tongue and groove exterior, the brick chimney, the fieldstone foundation and retaining walls also let it sit quietly among the homes that already filled the New England countryside. I think that is what I admire most about this house. It’s duality. This new architecture easily gave a proper nod to New England tradition without compromising its definitive modernism. Another stand out is the construction. Using materials familiar to the area, but not in the conventional way. One of my favourite examples of this is the exterior. The tongue and groove wood was applied vertically instead of the traditional horizontal. It was set so tightly that the joints between the boards became invisible and then it was painted white. This was a most thoughtful application as it makes the house from a distance appear to be clad in white plaster as their European modernist works. When you get close you can see the patterns in the wood so familiar to New England construction. This hybrid used to introduce the modern Bauhaus philosophy while complimenting what already existed in their surroundings, I would say was a complete success and something I haven’t really seen before. Such attention was put into both sides that this result would easily help introduce a new architectural approach to the New England countryside.

Full disclosure as I of course write from my own point of view in the here and now.. we were told that back in 1938, some of the more conservative neighbors thought these houses looked like nothing more than chicken coops! It is possible that New England is the toughest of crowds, and before you take me to task on that one, yes. I am allowed to say it. My mother is a staunch Red Sox fan and my Dad, well he loves the Patriots. I of course have no preference. Sports is not really my thing. Now where were we? Right, we were just entering the house.

Pictured above, the entrance to the house. It is protected by a marquee extending out from the north side of the building at an angle. From this view you can also see the spiral staircase leading up to the roof deck. Both of these elements break up the formal geometry of the front façade.

double desk made for the gropius' in the bauhaus workshops in dessau, 1925

Interestingly enough, almost all of the furniture in the house was made in the Bauhaus workshops in Dessau, 1925, for the house Gropius designed as part of the Bauhaus Family Housing, with a few exceptions. As a matter of fact, the Bauhaus furniture in the house is the largest collection of furniture from the school outside of Germany. How this came to be is an interesting part of Gropius’, of Bauhaus history. Since the Gropius’ were only on ‘a leave of absence permit’ from the German government, they could not take all of their belongings with them to London. Ise stored everything at her sister’s house in Berlin. Once the Gropius’ found themselves moving to the U.S. and Mr. Gropius with the job of implementing the Bauhaus method at Harvard University, it was of crucial importance to somehow get all of their belongings safely to the U.S. with them. During this time, it would be no easy feat. German architecture was controlled by the Goebbels administration. Goebbels was said to have “intensely disliked Gropius and all that he stood for.” Once again Gropius had to call on a friend. A professor in Berlin intervened on his behalf. He explained to Goebbels that for the first time in the history of German-American relations, a German and not a French architect was asked to lead the Harvard School of Design. In this case he thought it would be in everybody’s best interest to let Gropius take all of his possessions out of Germany to the U.S.A. Luckily Goebbels took this advice in spite of himself, and the Gropius’ were able to return to Germany briefly to pack their things and put them on a boat bound for New York. You see, it was not only furniture they retrieved. It was all of Gropius’ work, office files and correspondence from 1910-1937. Press references to him and the Bauhaus along with all published articles. Without this transaction the world would have lost much of the Bauhaus history, as the war took over Berlin in 1945. Today these important files are stored at the Bauhaus Archiv in Berlin, with copies given to the Harvard Library.

Now inside we are able to see where Ise and Gropius shared a study. The large double desk (evidence of the way the couple worked together) was made in the Bauhaus carpentry shop headed by Marcel Breuer in 1925. It was made to their specifications, with filing cabinets and special lamps to light the typewriter from above. I absolutely do not need to tell you that I would like to have these lamps, made by Marianne Brandt, if I remember what I was told correctly. The desk originally had upper cabinets which had to be removed to fit properly in this house, so as not to block the natural light and view from the window which runs the length of the study. The study chairs are Saarinen and the small book or magazine stand is one of the originals from the Isokon firm.

I kind of love that the Gropius’ surrounded themselves with objects that had meaning for them, even in their workspace. It is something that I wouldn't usually consider as I am of “clear desk, clear mind” mentality. We were told that they moved things around often, and much of the things they cherished were given as gifts or found during travel. I’ve looked at more than enough photos of this area in the house and one thing is always constant, the photographs of their granddaughters. They are always in the same place. Displayed where Ise only had to glance over to see them. If you look closer at the desktop photo you will recognize some of the artists/friends that have given the Gropius’ mementos over the time they lived here. A tile painting from Max Ernst, paperweights by Carl Auböck.. On the top shelf, three clay figurines given to the Gropius’ by Diego Rivera in Mexico City, 1947.

LIVING space off of study

THE PERFECT FRAME FOR SAARINEN'S WOMB CHAIR

DINING with BAUHAUS STYLE

OUTSIDE LOOKING IN

It is said that this house was built as a shell for the Bauhaus furniture the Gropius’ were able to retrieve from Germany. The house would serve as a showcase of Bauhaus design for students and colleagues. As we enter the living and dining room areas from the study, it becomes quite apparent the years have certainly brought a wide array of other modernist designers’ art and work into the home. The Isokon Long chair designed by Breuer was originally acquired by the Gropius’ in the late 1930’s. The one that sits in the house today is current production. All of the other furnishings and lighting are original to the house or were gathered by the Gropius family. We were told that the house has remained virtually unaltered save for a few repairs, and left at Ise’s request, as it might look on any normal day in 1967. Aside from the Isokon pieces, you also see Breuer’s designs from the carpentry shop of the Bauhaus in 1925. The daybed, side tables and dining room chairs for example. Other important designers share this space as well. When the Bauhaus founder traveled to Japan in 1954, he found the Japanese aesthetic profoundly inspirational. These original Sōri Yanagi Butterfly stools were designed the same year as his visit. He brought the two back and positioned them near the fireplace, a place of pride in the family home. The Saarinen womb chair was a birthday gift from Gropius’ friends. The Moholy-Nagy painting that hangs over the fireplace was gifted to the Gropius’ by his wife. Oil and etched lines on clear plastic. It is quite a thing to see outside of the traditional museum setting. It is left unframed and hung 1.5 inches away from the wall. This allowed for a perfect shadow image when the sun hit it. Magical.

The first floor is essentially one large room divided into three parts. The living room and dining room can be separated by a curtain. The transparent glass brick wall breaks up the dining room and the study. It is an interesting choice of barrier as it defines the space without enclosing it. The large plate glass windows allow the compact space to breathe.

The galley kitchen was outfitted with white metal cabinets, stove and refrigerator. In 1938 (now please consider the year) The General Electric Co. gave the Gropius’ a couple of “presents”. They installed both a dishwasher and a garbage disposal.. In case you missed that last bit, a garbage disposal. Just to be clear, the Gropius family had a garbage disposal in the year 1938. It is now 2018 and I do not have a garbage disposal. Granted, it is because the state of New York will not allow it, but that doesn’t make me any less jealous. Anyway, they gifted these to the Gropius’ as they were having a hard time selling them and thought that a house this forward thinking would have many visitors to see their products in action. Some early product placement in such a home was not a bad idea. Ise considered herself “well equipped to cope with a new situation” when her maid left to work in a munitions factory in 1941.

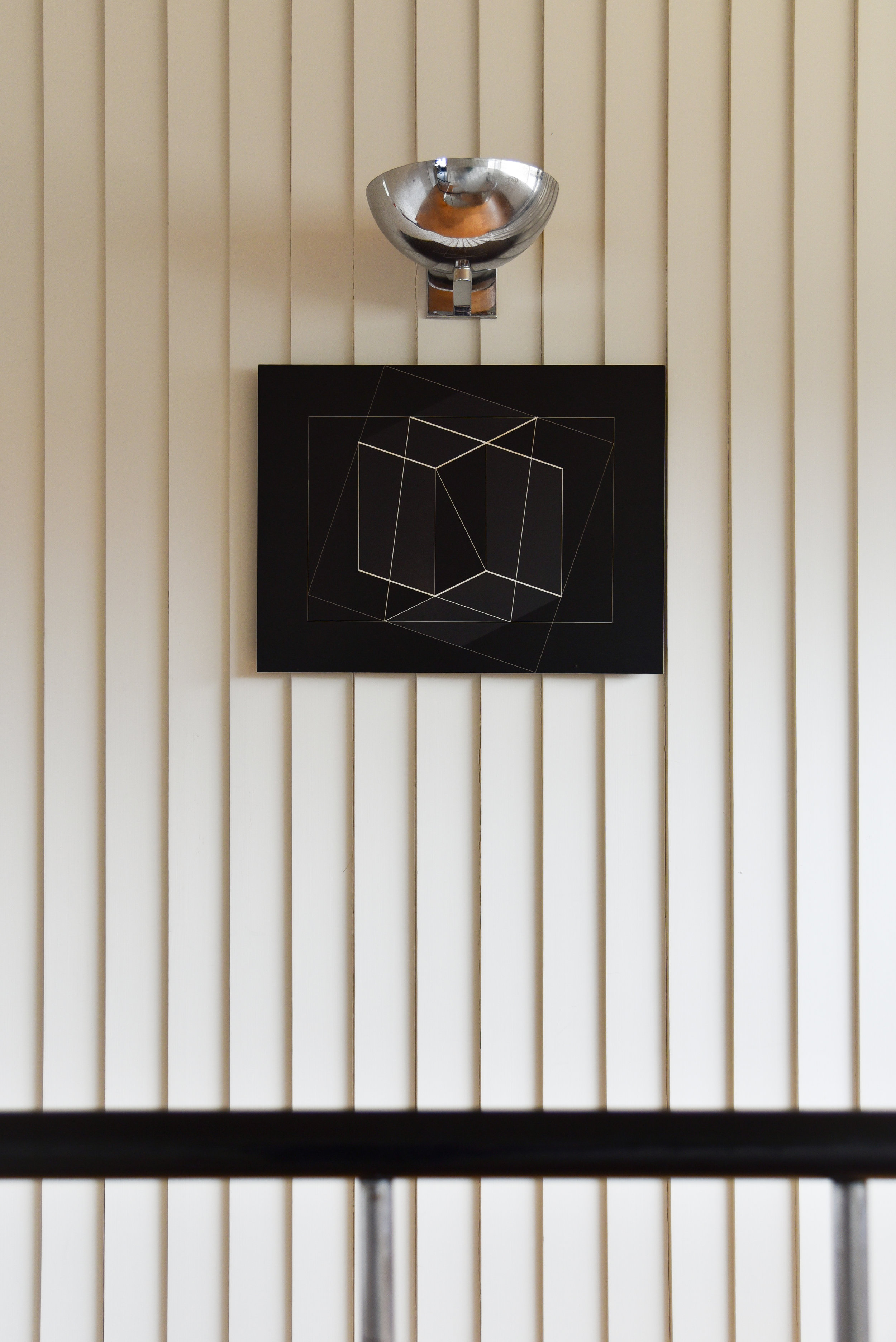

Up the curved staircase to the second floor - the family’s private quarters. A few things of note before we get there. One of the few custom fabrications in the house is the handrail for the staircase. A welder fitted metal pipes together and bent them to fit the curve of the stairs on site. The other, if I remember correctly, some outside lighting. The halls and stairs are covered in cork flooring installed for the material's resilience. Hanging prominently on the wall, artwork by Josef Albers. A good friend of Gropius from Bauhaus days, it was his 70th birthday gift from the artist. Throughout the house, and like no other I have seen, important works of art given to the couple by famously artistic friends are lovingly placed.

DAUGHTER'S ROOM WITH GROPIUS DESIGNED DESK

The desk in daughter Ati’s room was designed and used by Gropius first in the director’s room in the Weimar Bauhaus in 1922 and in Dessau until 1928 where it awaited its U.S transport from Berlin. This little desk has traveled quite a distance to have landed here in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Some of my favourite desk details, and.. lamp.

BED ALCOVE

So.. it seems I have a thing for small cozy spaces with room for a bed, some good lighting and a bit of Aalto. This alcove just does it for me. Enough said.

Here a couple of scenes from the Master bedroom. Since I do not want to sound too repetitive I will not say anything about things on top of night tables. I will tell you about a rather smart feature in both bedrooms. The narrow wooden slats you see on part of the wall to the right of the bed are for hanging artwork, photos, branches, just about anything without marring the walls with nail holes. Nails can be safely driven into the wood lengths so the plaster walls stay pristine. Opposite of the bed photo, a peek inside one of the closets. Shelving for both his and her accessories giving the items their own space behind a closed door.

roof deck

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. It is my favourite story from our visit to the Gropius house, and if you know me, you have definitely heard it. The roof deck is placed directly outside of their daughter’s bedroom. She asked for this so she could “sleep under the stars." Remember the spiral staircase at the front of the house? She asked for that, too. She wanted a bit of privacy when her friends visited. From what I’m gathering, there was someone that Mr. Gropius couldn’t imagine saying no to.

west elevation with screened in porch

“As to my practice, when I built my first house in the U.S.A. – which was my own – I made it a point to absorb into my own conception those features of the New England architectural tradition that I found still alive and adequate. This fusion of regional spirit with a contemporary approach to design produced a house that I would never have built in Europe with its entirely different climatic, technical, and psychological backgound.”

- Walter Gropius, Scope of Total Architecture